“Three Transitions” from 1973 depicts a slippery reality that thwarts the notion of video as an inherently “documentary” medium.

A major work of video art is turning 50 this year: “Three Transitions”(1973) by peter campus is now on view at Cristin Tierney Gallery for its monumental anniversary. The early 1970s marked a pivotal moment in the development of video art, as many of its key practitioners — including campus himself — began experimenting with the medium. Just as the invention of lightweight, portable film cameras revolutionized photography in the 1920s, mobile video cameras increasingly allowed for an entirely new way of accessing the moving image a half-century later. For the first time in history, human beings could see themselves instantly reflected in motion on screen, giving early video pioneers new tools with which to push the limits of self-representation. campus, like many of these artists, used this new technology to blur the distinction between subject and object, viewer and observer, in a way that has rippled forward into our own era.

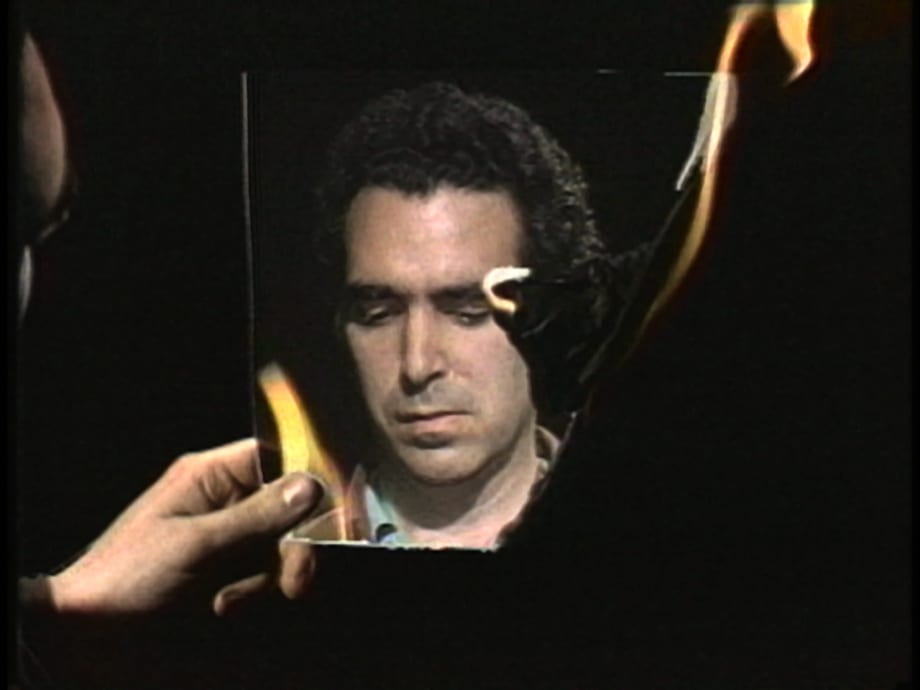

In many ways, “Three Transitions,” which is just under five minutes long, exemplifies this early tendency in video art. Produced during an artist residency at the Television Workshop at WGBH in Boston, it consists of three separate acts. Using the chroma key effect (the technique that’s behind the “green screen”), campus filmed himself simultaneously from the front and back. In the first “transition,” he appears to stab himself, slicing all the way through the rear of his jacket. He then sticks his hand through the slit, opening it wide enough that he is able to step through. In a second act of self-destruction, campus paints onto his face and erases it, only to reveal his face again doubled beneath the original projection. The video concludes with him appearing to burn the live broadcast of himself, which he holds in his hand like a portrait — an “anthropomorphic palindrome,” as Richard Lorber called it in 1974.